The International Council for Exploration of the Seas (ICES) released its latest advice on European eel on 7 November. Its advice remains consistent: “ICES advises that when the precautionary approach is applied for European eel, all anthropogenic impacts (e.g. caused by recreational and commercial fishing on all stages, hydropower, pumping stations, and pollution) that decrease production and escapement of silver eels should be reduced to – or kept as close to – zero as possible in 2019. ”

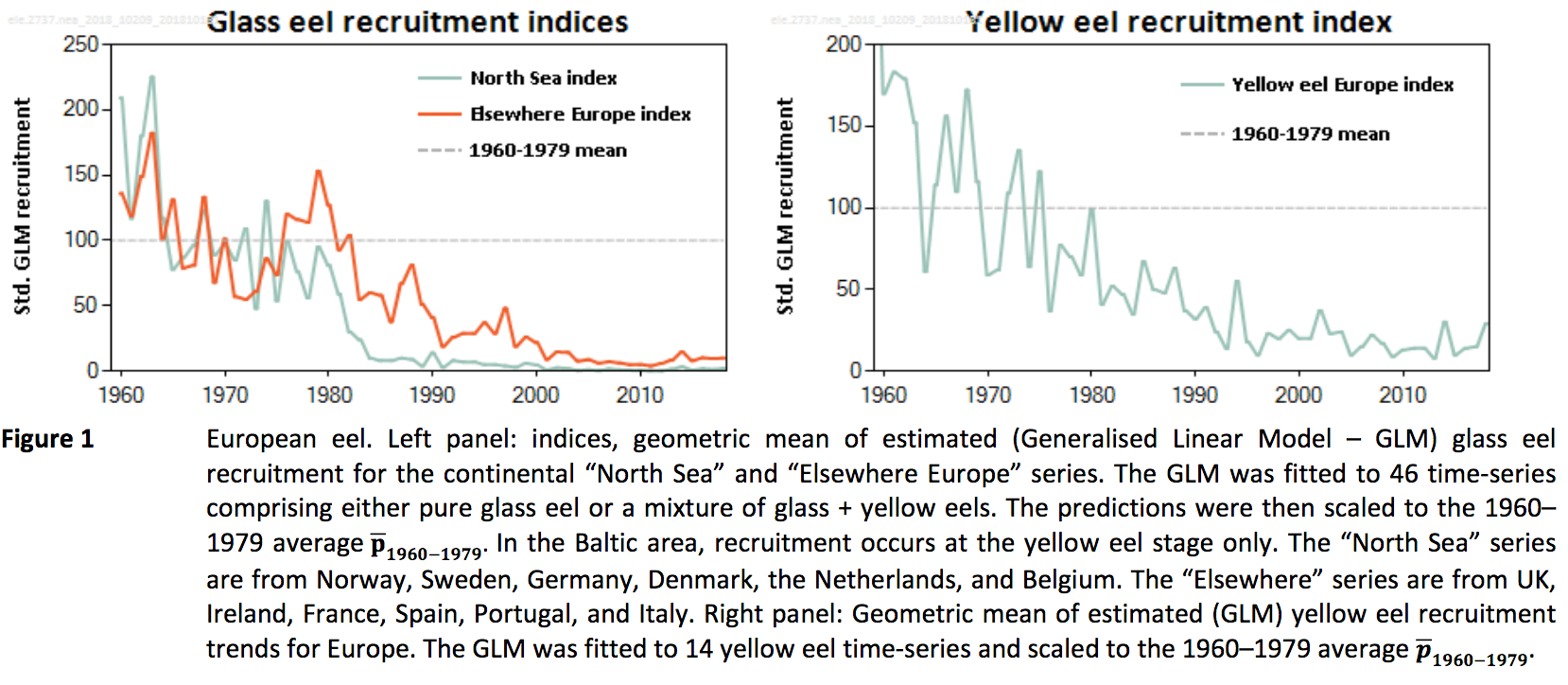

The status of the eel stock remains critical, with annual recruitment of glass eel in European waters at 2.1% in the North Sea area and 10.1% for “elsewhere Europe” compared to the levels in 1960–1979.

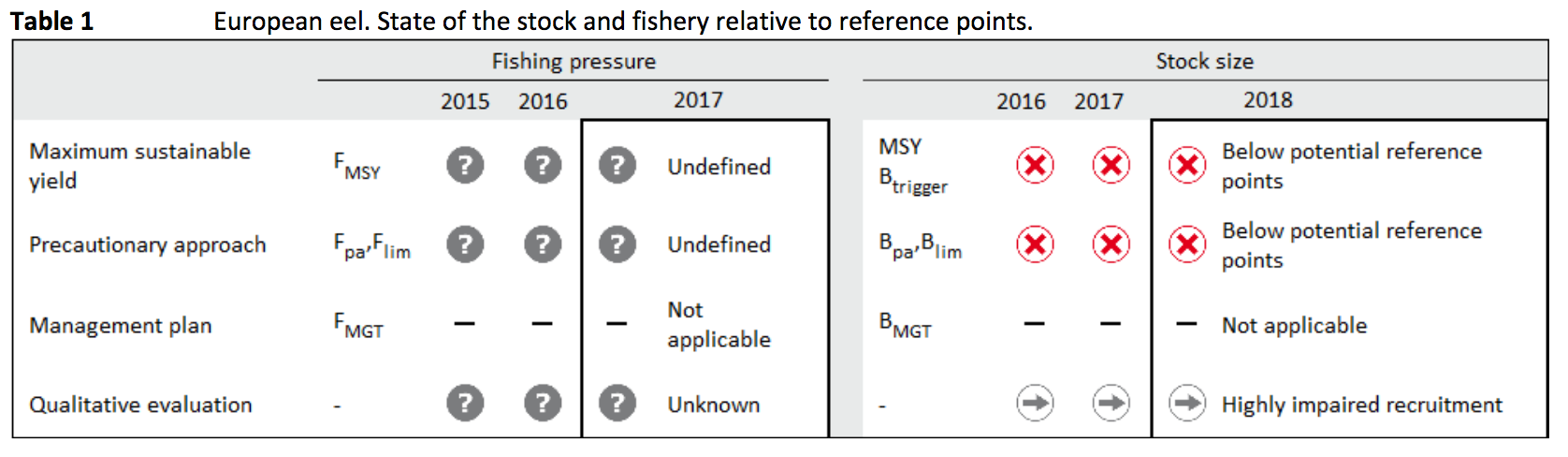

No stock reference points have been defined for European eel, so a normal assessment against either Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) or the Precautionary Approach (PA) – both used as management methods under the EU Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) – is not possible. However, ICES assessment is that the stock size is likely to be “well below potential biological reference points” for both.

ICES also reiterates that evidence on the contribution of restocking to actual spawning is missing and that internationally coordinated research is needed to determine if there are any net benefits on the overall population. Meanwhile, the advice is that “stocking should take place only where survival to silver eel escapement is high, and should not be used as an alternative to reducing anthropogenic mortality” [our emphasis].

Continued fishing on a threatened species

European eel is also the focus of a number of conservation measures. It is listed as Critically Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of threatened species. It is also listed under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in an effort to limit trade, as well as under Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS).

Despite this, it is still targeted in fisheries across most of the European Union, and despite long-standing inconsistencies in reporting by Member States, current estimates of commercial landings in the EU for 2017 are 67.1 tonnes of glass eel and 2 075 tonnes (not including Germany; 205 tonnes in 2016) of yellow and silver eels.

France completely dominates legal, commercial glass eel catches, and has even increased catches in recent years from 34 tonnes to 54 tonnes. A conservative estimate puts the number of glass eels in 1 kg at 3 000 individuals, resulting in an EU reported catch of 201 300 000 glass eels.

For yellow and silver eel, the picture of commercial catches is more mixed with the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, France, Denmark, Sweden, Germany, Italy and Poland all catching more than 170 tonnes in 2017. If you apply an average weight for silver eel of 1.5 kg to those catches, you get a very conservative estimate of 1 520 000 eels that are taken up before they have a chance to attempt spawning migration.

These are considerable amounts for a critically endangered species. There are many other anthropogenic impacts on European eel, but with these [albeit unreliable] catch figures for just commercial landings, it is hard to argue that fishing has no effect on the population.

The European eel recovery plan (EC 1100/2007) has been in place since September 2007, requiring Member States to ensure the escapement of 40 % of the pristine estimates of silver eel, in order to support spawning and recruitment. Since it came into force, the reported commercial landings of yellow and silver eels have declined from 3 056 tonnes in 2006, 2 613 tonnes in 2008 to 2 280 tonnes today. The [reported] catches of glass eel were 75 tonnes in 2006, 85.6 tonnes in 2008 and 67.1 tonnes in 2017.

Ten years after the implementation of the plan, there has been no significant improvements in recruitment. In terms of fisheries, they have decreased by only about 10 % for glass eel and 25 % for yellow and silver eel. Only Ireland has closed all eel fisheries since the recovery plan was put in place. The external evaluation of the EU management framework is expected next year.