The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) recently published its response to a European Commission request for advice on the seasonal migration patterns of European eel[1]. The paper contains an interesting summary of the knowledge that we have on migration patterns of European eel across the continent, including glass eel recruitment and silver eel escapement, but does not actually provide much advice on whether the current measures are having an effect or not, referring to data limitations and complexities.

The European Commission made a special request to ICES for advice on eel migration patterns in order to assess the effectiveness of the three-month fishing closures that were agreed by the European Fisheries Council for 2018/2019 and 2019/2020. It was also interested in any changes in eel migrations since the implementation of the European eel regulation began. The request for advice is part of Commission considerations of possible future measures to improve the protection and recovery of the European eel population.

ICES was asked to look specifically at when European glass eels arrive at different EU shores, as well as peak arrival, and whether this has changed substantially since the agreement on the eel regulation in 2007. ICES was also asked to look at when European silver eel in different EU regions begin their migration to the Sargasso Sea, when the peak of migration takes place and whether this has changed since 2007. The Commission also asked about when migrating eels need to pass through narrow passages, such as the exit from the Baltic Sea and to/from the Mediterranean Sea, and whether this has changed since 2007.

Most of the information that is available on eel movements is based on either monitoring programmes or commercial landings data. ICES also carried out a literature search.

Glass eel arrives gradually from October

The arrival of glass eel from the Sargasso Sea begins in October along the coast of Portugal and Spain, reaches France in November, and then progresses into the English Channel and the North Sea. The main migration lasts for four to five months. The arrival pattern in the Mediterranean Sea is similar, but much more uncertain; it starts in November and lasts until March.

Most fisheries landings in the EU are taken in the middle three-month period. Peak in glass eel fisheries per region:

- Southern Bay of Biscay (Spain/Portugal ): December to January

- Northern Bay of Biscay (Asturias): January

- English Channel: March

- Western and central Mediterranean: January

The seasonal migration pattern is more pronounced in the Atlantic than in the Mediterranean. Very little information is available on the timing of glass eel movements through the Gibraltar Strait.

We should remember that the arrival of glass eels is not an active migration from the Sargasso Sea. When the eggs hatch, the small, transparent fry gradually develop into transparent leaf-shaped larvae (Leptocephalus) and are carried from the Sargasso Sea on the surface of the Gulf Stream towards the coasts of Europe over a period of two to three years. It is only when they reach the warmer coastal waters of Europe and North Africa that they transform into glass eels and move towards the coasts and rivers.

No clear picture of movements of yellow eel

As the glass eels move from the surface and start to live in the vegetation closer to the bottom, they begin to turn yellow-brown and when this transformation is complete they are known as yellow eels.

ICES conclude that yellow eel does not undertake discrete migrations, but that there may be some seasonal movements, such as gradually moving upstream, or movements between fresh and salt water. The available data does not provide a clear picture.

Eels spend most of their life as yellow eels, growing until they reach maturity, which is 10–25 years in northern Europe and 5–15 years in southern Europe. During this period, they build up food reserves to cope with the long migration back to the Sargasso Sea. Before they set off, they transform into silver eels. The life cycle is shorter for eels in the southern part of the range than in the north, and therefore the age at which they transform into silver eels varies from four to twenty years of age (Feunteun, E. (2007). in litt. to IUCN/TRAFFIC Analyses Team, Cambridge, UK).

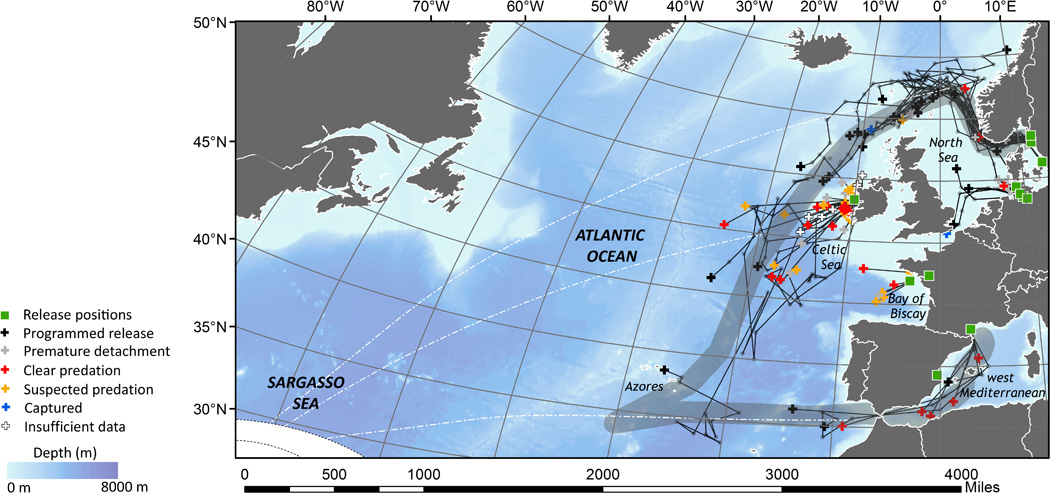

Many silver eels swim a long way

Migration of silver eel typically starts in early autumn and carries on during a longer time period, especially from areas further from the Sargasso Sea – the northern and eastern parts of the European continent. It stalls in the cold winter months, and may then resume in early spring.

Fishing for silver eel always takes place during the migration period, as the silver eel life stage is all about migrating to the Sargasso Sea to reproduce. Peaks in the regional silver eel landings are as follows (underlined is the greater amount):

- Western Mediterranean (Corsica): December

- Western Mediterranean (Spain): January to February

- North Sea/English Channel: September to October

- Baltic Sea: September to October

Extrapolating from movements in the Baltic Sea and rivers in the catchment area, silver eels pass through the straits from the Baltic from early autumn to the following spring. Less is known about silver eel migration from the Mediterranean through the Gibraltar Strait, with limited evidence that it takes place in the early spring months. Any potential timing of the silver eel passage through the English Channel was also not possible to determine.

Use of EU eel fishing closures

What the Commission ultimately wanted advice on was whether the current fishing closures are applied in the most effective manner to support the protection and recovery of European eel, and whether implementation of the Eel Regulation over the past 10 years has had any notable effects on eel migration patterns. ICES does not really answer these questions in the report, but nationally it is easy to compare the peak migrations with the fishing seasons, and draw some conclusions from that. In the Baltic region, for example, many countries have closed their fisheries in the November to February period, after the main fishing season.

The current EU wide three-month closures came about in 2107, when the European Commission proposed a complete ban of silver eel fishing in EU waters, which Member States rejected. Instead, a nationally implemented closure was agreed for the 2018/2019 fishing season, restricting the commercial fishing for eels above 12 cm in EU waters over three consecutive months, between 1 September 2018 and 31 January 2019 – to be introduced by each Member State.

In 2019, this closure was expanded to include all eel life stages, and commercial as well as recreational fisheries in transitional and EU waters, for three consecutive months sometime between 1 August 2019 and 29 February 2020.

Not possible to assess changes in migration patterns

In the end, ICES was not able to assess if there are any spatially distinct changes in migration patterns since the implementation of the eel regulation began. It concluded, however, that whereas one fishery did not follow the 3-

month closure in 2018/2019, 35 fisheries didn’t follow it in 2019/2020. Which countries these fisheries were based in is not spelled out, or whether the lower compliance in 2019/2020 is due to the increased coverage of the closures or not.

ICES also suggested that if seasonal closures are to become a significant tool for eel conservation and management, the routine data calls have to be expanded to include monthly landing figures. ICES still faces significant data challenges, with some countries not submitting full reports.

[1] ICES (2020). EU request on temporal migration patterns of European eel (Anguilla anguilla) in all relevant ecoregions. In Report of the ICES Advisory Committee, 2020. ICES Advice 2020, sr.2020.01. http://www.ices.dk/sites/pub/Publication%20Reports/Advice/2020/Special_Requests/eu.2020.01.pdf