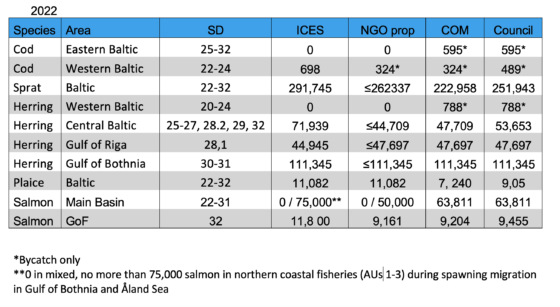

Negotiations of the 2022 fishing quotas for the Baltic Sea took place at the Agrifish EU Council meeting in Luxembourg on 11-12 October 2021. Several of the agreed fishing quotas are in line with scientific advice of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) and only bycatch quotas were set for eastern Baltic cod and western herring, for which a zero catch advice has been given for several years now. At the same time, ICES catch advice for Gulf of Riga herring, which is a well-managed stock, was higher than last year, and the quota was pushed above the scientific advice in the negotiations.

The European Commission’s proposal for the Baltic Sea fishing opportunities for 2022 demonstrated a serious attempt at implementing ecosystem-based management, including inter-species considerations, as is legally required by the CFP, the Baltic multiannual plan (BALTIC MAP) and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive’s (MSFD) qualitative descriptors for determining good environmental status (GES) stressing safe biological limits, functioning food webs and full reproductive capacity. The fishing opportunities for sprat and herring aligned with the lower levels of the ICES advice to leave room for cod to have enough to eat, as cod prey on both sprat and herring.

Unfortunately, the Council negotiations did not follow through on this ambition and the final results were an increase in the sprat catches and less of a decrease for central Baltic herring; a stock that has been severely depleted over the last ten years due to scientific miscalculations of the spawning stock biomass (SSB), as can be further explored here. Nevertheless, the total allowable catch (TAC) of central Baltic herring was still decreased by 45%, a necessity to give the stock a chance to recover. Moreover, the TAC of herring in the Gulf of Bothnia was allowed a large increase due to a scientific recalculation of the SSB, all in line with the ICES advice and the European Commission’s proposal. However, coastal fishermen have raised concerns about a shortage of large herring in the coastal waters, and how this increase in catches will affect the small-scale fisheries in the northern Baltic Sea is yet to be seen.

The most important outcome, which really illustrates the deterioration of both the environment and many fish stocks in all of the Baltic Sea, is a prohibition of all targeted fishing for cod in the Baltic Sea – both the eastern and the western cod populations are now in such bad shape that only a small bycatch quota is allowed. Restrictions of recreational fishing for cod also apply in subdivisions (SDs) 22-26. After years of mismanagement, the iconic Baltic cod has finally hit rock bottom. In light of this, the 25% increase of the TAC for plaice is an issue of concern, since cod is a common bycatch in the plaice fishery. If the use of selective gears in the flatfish fishery is not made mandatory, and introduced rapidly, this might be another severe threat to the cod.

The western Baltic herring, partly living in the North Sea but migrating into the Baltic Sea, has also been under stress for a long time and for the last four years the stock has been given the scientific advice of zero catch. This year, for the first time, the Council agreed on a TAC of bycatch only, with a few exemptions for small-scale fisheries.

Yet another unexpected outcome of this year’s negotiations was the TAC for salmon; all commercial catches of salmon in the open sea in the southern Baltic Sea (below Stockholm) will be prohibited. For recreational fishing, only catches of fin clipped reared salmon will be allowed, with a bag limit of one salmon/day. In total, 63,811 individual salmon may be caught, which follows the Commission’s proposal. In the Gulf of Finland, a total catch of 9,204 individual salmon will be allowed. Anglers and environmental organisations have been fighting to close the mixed salmon fishery in the open sea for decades, due to the risk of overfishing weak and threatened populations – the salmon migrate from the rivers out to the open sea and then return to their birth river to spawn. Hopefully, this milestone decision together with focused management measures to aid weak populations will lead to a broader recovery of Baltic salmon than we have seen so far.

Over and all, the EU Agrifish Council watered down the strong, ecosystem-based proposal from the European Commission, but some important decisions for a better future of the Baltic Sea were still made. Nevertheless, it is clear that the Baltic Sea ecosystem is in distress, as is the fisheries. The three most important stocks are under harsh protective measures, with a complete ban of targeted fishing for both cod stocks, western Baltic herring and salmon in the open sea.

Baltic TACs in 2022